“No, the wolf hasn’t been reintroduced”

Repopulation: a persistent myth

In Europe, wolves have never been reintroduced to an area. The expansion of the wolf in Italy and in the Alps, as well as in other European regions, in the last forty years is the result only and exclusively of the natural dynamics of the species.

Rumours of wolf releases by humans appeared, because some individuals showed up far away from the nearest packs. Many people could not imagine that wolves can cover such large distances on their own. The problem is, we humans tend to underestimate this species’ ability to move. Many people think that just because they cannot drive or take a train, wolves should be condemned to spend their lives within a few square km. Some terrestrial species, including the wolf, are able to travel great distances: in their own territory, they can cover tens of kilometres in a single day; when they disperse, they can make several hundred kilometres within a few months.

Long-distance dispersal is a characteristic behaviour of the species and is a dynamic and gradual process in which subadult wolves abandon their natal pack and territory. They search for a new, suitable territory and for a wolf of the opposite sex to reproduce and form a new pack. Dispersing wolves often cover great distances, sometimes through plain or hill landscapes that are much more inhabited by people and covered with settlements, where dangers for a wolf are much greater (traffic accidents, etc.), than in the mountains. The mortality rate of these animals is therefore high.

Thanks to the phenomenon of dispersal, starting from the few dozen wolves which survived in Italy in some areas of the central-southern Apennines in the 1970ies, generation after generation, the species has regained the territories from which it had been eradicated (in the Alps, at the beginning of 20th century).

How do we know that?

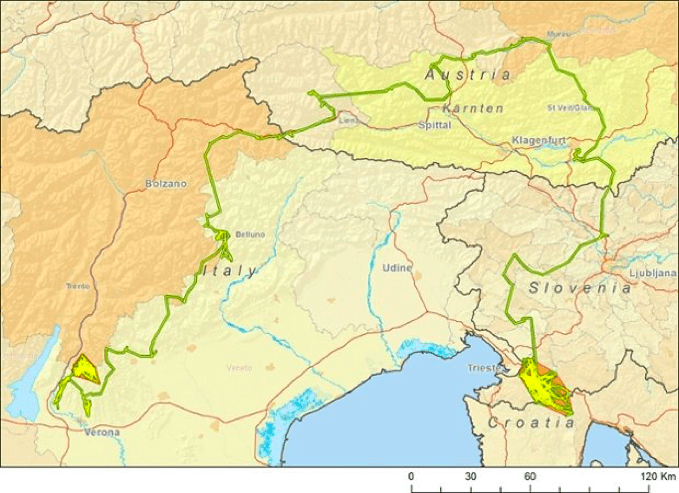

It was possible to document numerous dispersal events in the Western Alps (as shown in the image taken from the Report of the Piedmont Wolf Project by Marucco et al. 2010), through genetic analysis on biological samples (e.g. scats, tissue, hair) that wolves leave behind. The “nodes” on the map represent the places where biological samples belonging to the same wolf are named by a unique code (CN-M100) which also identifies the sex of the animal, male (M) or female (F):

In addition, some wolves were captured (for research purposes or because they were found injured in the wild and then recovered) and released again with a GPS radio collar, an instrument capable of transmitting the position of the animal in real time, so as to follow its movements in detail. Among the most famous documented dispersions there is that of the wolf “Ligabue”, from the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines to the Ligurian Alps (described in Ciucci P. et al. “Long-Distance Dispersal of a Rescued Wolf from the Northern Apennines to the Western Alps”, Journal of Wildlife Management 73(8): 1300-1306):

More recent and equally famous is the dispersion of the wolf “Slavc”, which from Slovenia reached, after a long journey, the plateau of the Lessini Mountains, where in 2012 it formed with the female “Juliet” the first pack consisting of a wolf of the Dinaric population and of a wolf of the Alpine population, documented by the researchers of the University of Ljubljana within the LIFE SloWolf project:

Sure, in the last forty years we have indirectly encouraged the return of the wolf in many areas in three ways: 1) by granting it legal protection at national and international level (at one time the wolf was considered a harmful animal and, as such, its elimination was promoted); 2) by abandoning en masse the countryside and mountains in some regions of the Alps, which have become depopulated and covered with woods; and 3) by favouring the restoration of ecological conditions suitable for the presence of a large predator by e.g. introducing wild ungulates (wild boar, roe deer, fallow deer, red deer) in Italy or increasing their density in other countries such as Austria.

Conclusion: The current expansion of the wolf is in any case the result of natural dynamics of the species, no reintroduction has ever been operated in Europe.