Why is it important to know what wolves eat? The study on the first pack on the Alessandria plain

The analysis of the diet of carnivores is of fundamental importance not only from an ecological point of view but also from an economic and social one, due to the conflicts that arise with human activities, from the livestock sector to the hunting world, as the species is often considered a threat both when it preys on domestic livestock and wild ungulates. Knowing its diet in particularly sensitive areas such as the plains, where anthropogenic density is high and livestock farming is numerous, can be a further step towards understanding this species and, hopefully, towards a more peaceful coexistence with it.

This is why in 2021 two thesis projects of the Dipartimento di Scienze della Vita e Biologia dei Sistemi of the University of Turin, within the framework of the LIFE WolfAlps EU project and in collaboration with the Ente di gestione delle Aree Protette del Po piemontese, were carried out to describe the habits of the first wolf pack to settle in the Piedmont plain, to be precise south of the city of Alessandria, near the Orba stream. In particular, the research carried out by thesis students Francesca Marras and Fabio Savini – under the supervision of Prof. Francesca Marucco – constitutes the first study on the ethology and ecology of the wolf in the plain, in a highly anthropized and fragmented environment.

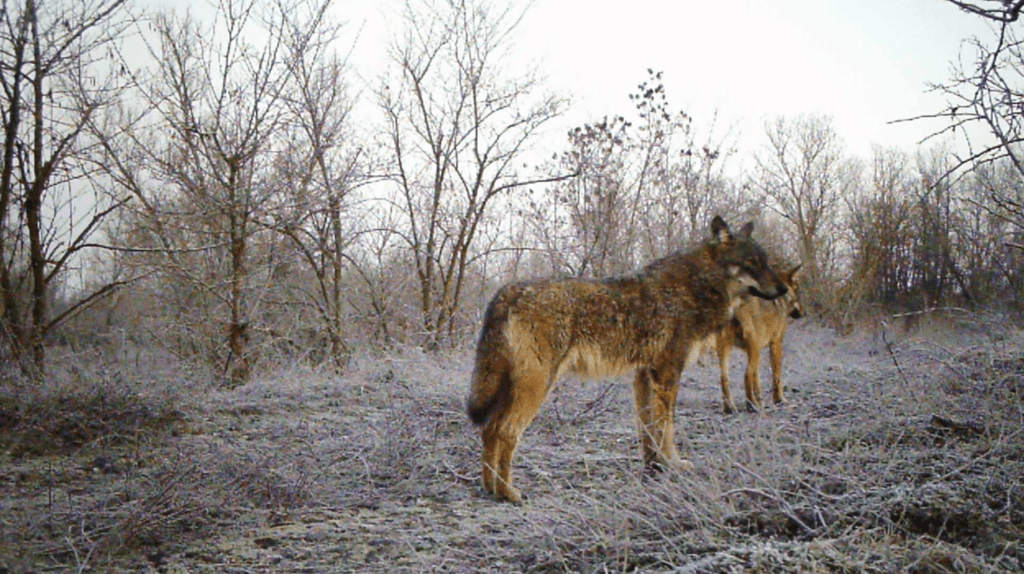

The first evidence of the presence of a wolf pack in the area came in November 2019, when an individual was spotted by a civilian in the hamlet of Retorto near the municipality of Predosa. Since then, technical staff and park rangers from the Piedmont Po Protected Areas Management Authority have been systematically following the pack.

In particular, the study area of Dr. Marras’ thesis project, which focused on the analysis of the carnivore’s diet, included an area of approximately 300 km2 located within the province of Alessandria, a few kilometers south of the city. The area is characterised by mainly flat areas to the north, and hilly areas to the south marked by the course of the Bormida river and the Orba torrent, where the Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and Special Protection Area (SPA) IT1180002 “Torrente Orba“, a site belonging to the Natura 2000 Network, is also located. More than 70% of the land use is occupied by polycultural areas, almost 10% by urbanized areas and only 13% by wooded areas.

The collection of droppings, which are essential for the analysis of food ecology, was carried out in winter, from January to April 2021. 124 km of systematic transects were repeatedly covered, most of which coincide with paths and dirt roads, not only because it is impossible to cross cultivated fields on foot but also because the wolves themselves mark and use regularly beaten paths in order to save time and energy. In total the distance covered for the search was 867 km, which made it possible to collect a total of 107 droppings, almost all of which were found on the banks of the Torrente Orba and in the area where it flows into the Bormida, north of Casal Cermelli.

Genetic analysis was carried out on a small sample of excrement made it possible to identify all the members of the pack: the reproductive couple, i.e. the male and the alpha female, and four female daughters, but also to rule out the presence of any other individuals.

The prey with the highest frequency of occurrence is roe deer (58%), followed by hare and mini-hare (lagomorphs 13%) and nutria, or coypu, (11%), for the first time documented in Piedmont among wolf prey. Wild boar constitutes less than 10% of the diet, as does sheep, the only domestic ungulate to appear among the main food categories found in the diet of the pack.

Among the most relevant results is the evidence that the diet of the wolf, even in a highly anthropized and human-influenced environment such as the study area, is based, despite the large presence of livestock in the area, almost exclusively on wild animals (92% as shown in the graph) and is not dependent on resources derived from human activities.

This confirms the markedly wild behaviour of a pack that, while living in close contact with humans, maintains its role as a top predator at the top of the food chain even in lowland environments.

“Despite the dozens of kilometers we travelled and the large number of tracks we found, we never came into direct contact with the wolves of the pack,” says Francesca Marras. “Only on one occasion did we come across a few specimens along the banks of the Orba torrent, but at the sight of us the animals disappeared instantly. Casual sightings of wolves on the move along roads and fields have been reported by the local population, but this does not necessarily imply a direct danger for domestic animals and pets, as the results of the research show”.

For more details, the thesis can be downloaded from the Centro Grandi Carnivori website.